Interview with Slava Kurilov, the Soviet sailor who swam to freedom (1974)

Slava Kurilov left Soviet Russia in 1974 in a way that reads like a sea legend: he bought a ticket on a government cruise liner and jumped overboard in the Pacific, then swam to a Philippine island. The story is equal parts political decision, personal conviction, and raw physical endurance. Below is a question and answer account in Slava's own conversational voice, covering why he left, how he planned (and did not plan) the escape, what he carried, how he navigated at sea, and what happened on shore.

What made you decide to leave Soviet Russia in 1974?

It was the same reason people leave any communist country. You cannot live there freely. Also I had an intuition about timing. I was in Semipalatinsk, near a very famous nuclear polygon where they made explosions every day. I felt something like Chernobyl could happen. Spiritually it was hard to stay, and I had a romantic desire to see other parts of the planet.

How did you plan your escape?

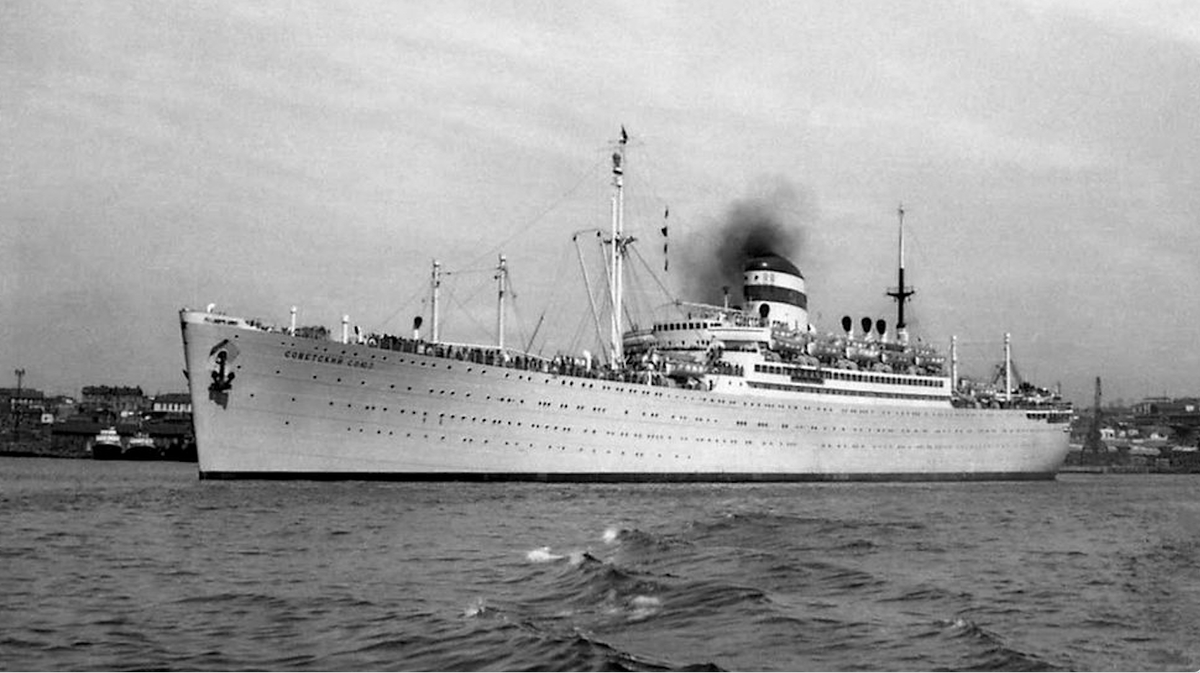

I cannot say I planned for months. The decision was made in one second, but getting ready to be ready took time. I bought a ticket on the biggest Russian liner called Soviet Union. It was a cruise to the Equator with more than twelve hundred tourists and no scheduled port calls. My idea was simple: if the ship would not stop, the only way out was to go into the sea and make it to land by myself.

How did you decide where and when to jump?

When we passed the Sea of Japan I looked at the route map. The cruise ran along Taiwan and the Philippines toward the Equator. I calculated two possible exit points: near the island of Saral or the south point of Mindoro. It had to be nighttime. I chose near Saral once we were in the right area.

Just a snorkel, a mask and fins. That is all.

I am a little crazy and romantic, yes. I had experience: I was a driver, oceanographer and navigator. The night I jumped it was stormy, thunderstorm from the west. I made sure to jump far from the propeller. I jumped at night so no one could see me. Everyone on board was dancing; there was a big party that night.

At sea: navigation, endurance, and danger

How did you know which way to swim when you lost sight of the ship?

At first I could see only the ship lights; the clouds hid the stars. I waited for the stars. After about two hours Jupiter showed through the clouds. That gave me direction. I also used the clouds' movement across the horizon to judge orientation and the development of the sky.

How long were you in the water?

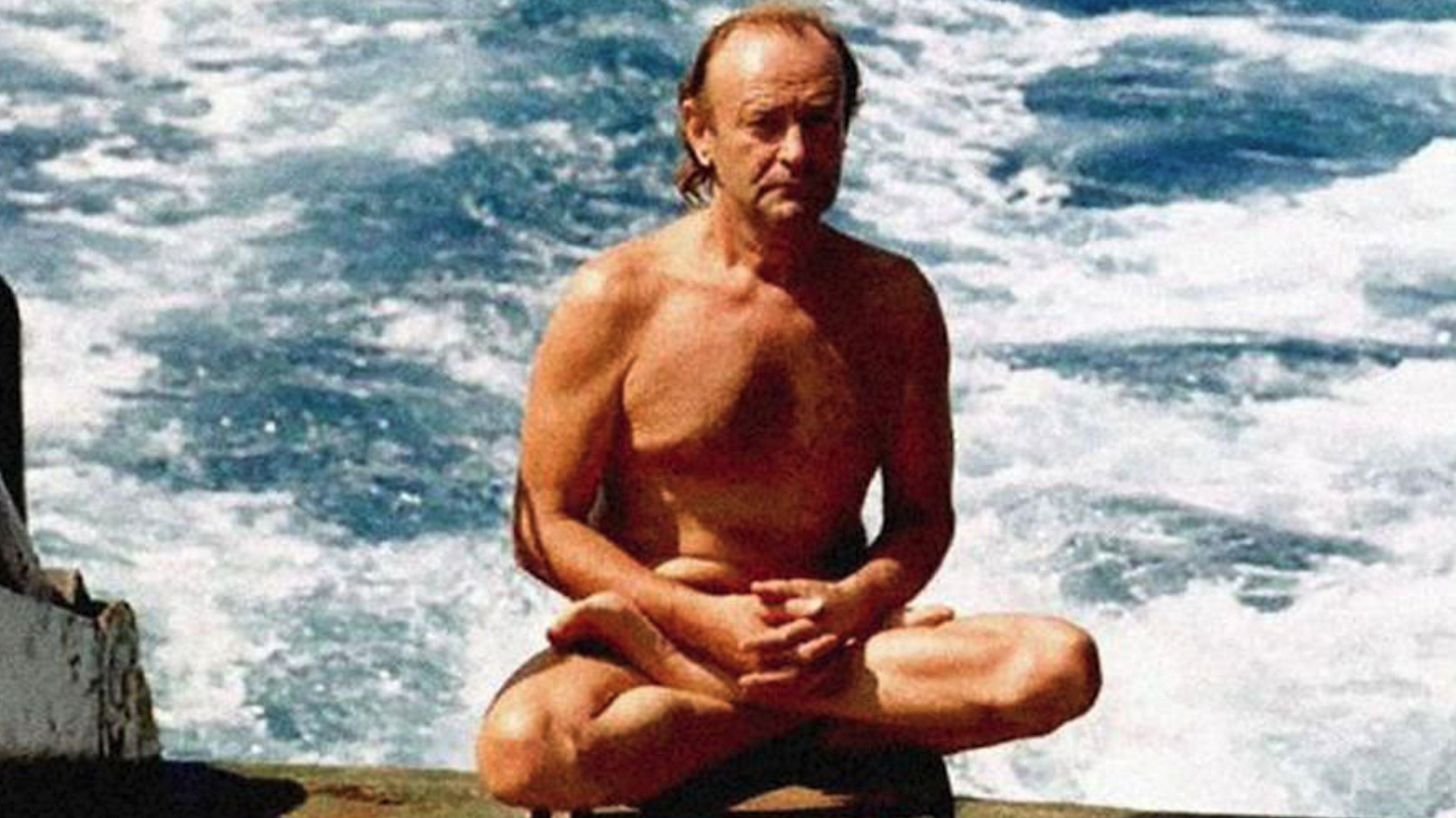

Two days and three nights. I had no food or water, but I had prepared: I fasted for thirty-six days before and practiced being without water for two weeks. It was not easy, but my body was used to it.

Did you try to rest? Were there sharks or other dangers?

I could not sleep; the harder part was staying awake in water. I knew about sharks; I had met them before in the Black Sea. The trick is to be calm, to behave like you belong to the ocean. I had to keep swimming because I expected currents. If you rest at the wrong place, a current will take you far away.

Did you ever lose consciousness?

There was a point near the island when a current took me back to open ocean. That third night I lost hope and lost consciousness. But later big waves near the reef woke me. I was under a wall of water maybe ten meters deep and came through it because I had experience with rough seas and surfing.

Arrival, first contact, and the aftermath

I arrived in a calm lagoon and could not sleep because I was too excited and the insects kept me awake. I walked along the island and met a fisherman with children. They were afraid because I was covered in phosphorescent plankton — I glowed. The children touched me slowly to make sure I was human.

At first they were afraid and thought I might be a spy. The local authorities investigated me as a possible Russian spy. I spent about a month and a half in prison, but the Filipino people treated me kindly overall. I ended up staying in the Philippines for about half a year before making my way to Canada.

Later life and reflection

I wrote the story and found a publisher in Israel. Many of my friends from Soviet times were Jewish, and when the story found its way there I was invited. I liked the country, the climate, and the people I met. I decided to stay.

Knowing what you know now, would you do it again?

I would do it again if I had to. It would be more difficult today, and I am not sure I would survive another time, but if I found myself in prison again, I would take that chance. We always have one chance.

Takeaways

- Escape can be a single decisive moment built on long internal preparation.

- Practical skills — navigation, ocean experience, mental discipline — can turn a risky idea into survival.

- Human kindness matters: strangers on a remote island ultimately helped, even through initial suspicion.

- The story became a memoir that connected cultures and led to a new life in Israel and Canada.

"Always we have one chance."

Keywords: Slava Kurilov, Soviet Russia, escape, swim to freedom, Semipalatinsk, Chernobyl, cruise ship, Philippines, fasting, prison, Israel, memoir, Unending Swim to Freedom.